First published in the Guardian, August 26, 2014

“We demonstrated that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

– the late Republican senator Howard Baker (Tennessee), co-sponsor of the Clean Air Act of 1970

A wise Grenadian recently asked me this very clear question:

My country is poor and we recently discovered oil, which will make us richer. Why should this oil be restricted or more expensive to exploit when your nation’s oil boom paid none of its environmental expenses?

A Chinese high school student recently asked me this similarly clear question:

My country’s manufacturing base means that my family moved from abject poverty to the middle class, and in my nation, hundreds of millions of others have done the same. Why should this manufacturing be more expensive by having to pay a cost for carbon when your nation’s manufacturing boom did not?

I grew up in the1960s, a decade when my family, my New York City neighbors, and tens of millions of other Americans were catapulting from poverty into the middle class. It was a great feeling. For perhaps the first time in modern history, large swaths of our society had enough money to purchase homes, spend on surplus and luxurious foods, hire household help, take vacations and buy new stuff on a regular basis.

This social and economic mobility was the envy of much of the world. And I’m certain the accompanying optimism helped open our hearts and minds to the great human rights revolutions of the past 50 years.

There was a shadowy side to this extraordinary period in American manufacturing, consumption and innovation, of course. Deadly air pollution in Los Angeles killed or sickened tens of thousands in the 1940s. Ohio’s Cuyahoga River caught fire a dozen times in the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1970s, it was discovered that industrial solvents buried in the ground were causing rampant birth defects in the Love Canal neighborhood of Niagara Falls, New York.

American consumers and industries behaved as if the air, water and land were our inexhaustible dumping ground.

We largely still behave this way. But now most of our manufacturing occurs elsewhere, which only complicates understanding this un-virtuous circle. China manufactures most of our stuff – and we criticize China for the pollution this creates. But the only reason America’s air and water have become as clean as they are is because some visionary Democrats and Republicans (with the support of a burgeoning environmental movement) worked together in the 1970s to pass the Clean Air and Water acts, highlights of American legislative history.

Cleaning up our air and water pollution remain ongoing challenges, but at least there are legislative benchmarks for guidance and enforcement.

Today we must fight for a worldwide price on carbon just as Americans fought for restrictions on air and water pollution generations ago. This is the only way to level the international business playing field so the biggest polluter does not make the biggest profit.

There is no us and them when it comes to air, land and water. These basic elements of survival are all approaching their limits at just the same time as the next billion people are becoming new consumers and leaving poverty behind. Something’s gotta give.

Which takes us back to the thorny questions raised by my Grenadian and Chinese colleagues. Who’s gonna pay for the transition to a low-carbon economy? Those of us who caused today’s problems, or the billions of people whose regions are finally poised to rise out of poverty? This debate is part of what’s holding up a new United Nations climate treaty.

In December 2015, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is supposed to adopt a new treaty to replace the Kyoto Protocol, which expired in 2012. Between now and then, nations will be jockeying for position on a variety of issues, perhaps most contentious of which is the Green Climate Fund.

This bucket of money is meant to be filled by nations already wealthy on centuries of greenhouse gas pollution, to fund low-carbon economy investments in India, Brazil, South Africa and other developing economies. This subsidy will empower these nations to sign on to greenhouse gas emissions cuts in a new global treaty, and will – it is hoped – enable their citizens to rise into the middle class without making global warming any worse. This fund is the major stumbling block to a signed global climate agreement.

I know this feels wrong to Americans in so many ways. Our middle class is being eviscerated and so many are seriously suffering. Our economic dominance is waning. The United States is no longer the preeminent world power. And we’re gonna help others compete?!

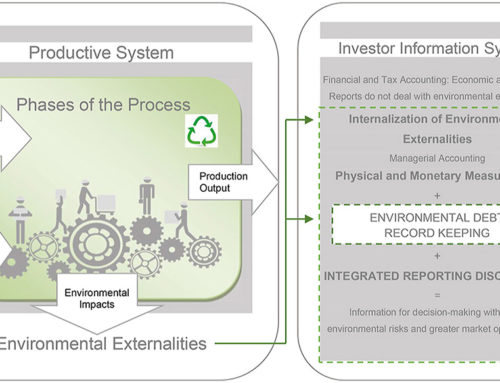

Well, yes, if we want to avoid climate chaos and survive with a habitable planet. Think of it as the environmental debt we are carrying – and the bill is due. Those of us who benefited from the industrial and technology revolutions must now sacrifice some of our wealth so that the next billion people can choose clean technology as they develop their economies. These payments will sound like stealing food from your children when they are debated on cable television and talk radio, but in reality will amount to a rounding error for the US government budget.

The world’s nations have passed several landmark treaties despite threats of economic chaos from industry. The Montreal Protocol banned chlorofluorocarbons and prevented a catastrophic hole in the ozone layer. The Biological Weapons Convention banned a whole class of weapons of mass destruction.

Certainly transparency and corruption must be addressed before the Green Climate Fund is viable. But progress on transparency just inspired Germany (which gets 74% of its energy from renewables) to commit $1bn to the fund.

Here’s the thing: the Green Climate Fund will recover its investments in short order. Clean technology will be cheaper in the long run for two reasons.

First, low-carbon technologies like wind and solar energies are rapidly decreasing in price and increasing in efficiency – at the same time that electric vehicles are exploiting smarter financial models, and farmers big and small are pursuing a low-carbon agricultural revolution.

Second, the cost of pollution-intensive technologies is staggering. Emergency services, spill clean up, illnesses, pipeline security, boom and bust economic cycles, marine dead zones and extreme weather – we already pay an exorbitant price for carbon. In 2011, a Harvard Medical School study found that while coal’s low price as an energy source seems like a bargain, burning coal actually costing the American economy $175bn to $523bn a year in pollution, lost tourism, climate change impacts, and health effects like premature deaths and cancer. That’s real money.

The US and the rest of the industrial nations got rich first and caused a big load of environmental trouble for the entire world. Now, as the rest of the world wants to get rich – who doesn’t? – we have to pay for the problems we’ve caused. The Green Climate Fund is the bitter pill that will make all of us healthier.

The United Nations has its time and place. I’d contend that when it comes to climate, now is both. The world’s nations can again do something great. We must find our political will to help make it so.