First published in the Guardian, August 18th, 2014

Like so many of us, I have personal experience with cancer. I’ve had it twice, and so have both of my parents, six aunts and numerous friends. Just last month, someone very close to me was diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. These illnesses are more than just statistics. They require the patient, as well as their families and friends, to journey through a pretty broken medical system, and their emotional price is exorbitant.

My own cancer odyssey started about eight years ago and lasted two years. (I’ve been cancer-free for six years now and I’m doing fine, thanks). When I started feeling physically better, I felt the release of an emotional bottleneck. I went to a support group and each of the six people there told the same story: “I’m sure I got cancer for a reason and I just don’t know what it is yet.”

I responded, perhaps inappropriately: “You got cancer because a variety of companies, governments and shareholders decided that clean air, water and food were less important than their money.”

I’m sure everyone in that group was happy I never returned, but it was a great catharsis for me. At that moment, as an environmentalist working with business, my emotional self met my professional self on very clear terms. I realized we must begin including the environmental costs – including environment-related health costs – in every financial transaction.

Consider this: last year, the US spent $37bn on cancer drugs and over $100bn on cancer treatment alone. Those numbers don’t include the unreported and uncovered costs, such as nurses, acupuncture, psychotherapy, personal travel, supplements and caregivers’ expenses. I spent many thousands of dollars in such costs for each of my cancers, and that’s far from unusual. Of course, those numbers also don’t include the personal costs borne by families and individuals, nor the follow-on effects of cancer treatment in the form of future weaknesses, illnesses, lost wages and lower productivity.

I have grieved and tended too many friends who had cancer in their 30s and 40s, and feel absolutely certain that chemicals, drugs and hormones in the air, water and food play a role in causing this scourge. Reading about the cancer cluster of kids in Toms River, New Jersey, illustrates the difficulty of proving these connections, but for anyone reading the news or sitting by a sick bed, these connections are palpable – and science is getting closer to proving it.

Air pollution kills as many people every year as smoking does, according to Brigham Young University economist C Arden Pope III. Meanwhile, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer lists 113 agents that are carcinogenic and 66 that likely cause cancer. These chemicals range from the familiar villains – such as tobacco, asbestos and formaldehyde – to the lesser-known fuchsine for magenta production and vinyl chloride used to make the ubiquitous PVC found in industrial pipes, plumbing, packaging and credit cards.

But external environmental and social costs – including health impacts – of these chemicals aren’t often considered in the financial equations that result in their use in many products today. The costs of cancer simply don’t show up in the balance sheets of the businesses that contribute to its prevalence.

GDP, for example, is one of the most important economic indicators in use. All the health care spending I mentioned earlier actually contributes to the GDP, showing up as a positive sign in the profit-and-loss-only model of economic health. When economic growth causes increased illness and healthcare costs, our measurements are missing some basics. It’s not always so great when the GDP goes up. A thriving economy needs a healthy society, not more cancer spending.

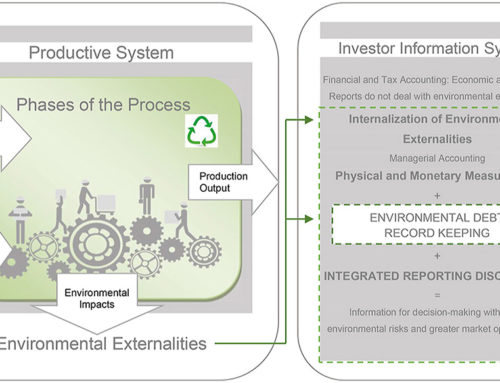

We need to construct a new financial ledger. To calculate true profit and loss, broader societal and environmental causes and effects need to be added into the equations. In other words, we need integrated reporting that includes the external environmental and social costs – including health impacts – currently not on the books.

There are signs that some businesses are starting to think about these costs, whether or not they’re including them in their financial statements. Take CVS Caremark, which earlier this year unilaterally decided to forgo $2bn in annual tobacco sales because of the negative health impacts. In a recent column in the Guardian, Eileen Howard Boone, senior vice president of corporate social responsibility at CVS Caremark, wrote: “What we saw was a health epidemic with 480,000 tobacco-related deaths each year, and a $300bn annual economic wallop attributed to smoking.” The company simply looked at the toll tobacco takes on society and – in a courageous move – decided cigarettes didn’t fit into the mission of a healthcare company.

But more needs to be done. Ounces of prevention, in this case, are worth thousands of pounds of cure. Reducing the environmental factors that contribute to cancer could have benefits that ripple across all business – transferring costs from a stressed and broken healthcare system to bolstering the quality of our food, water, clothing, indoor and outdoor air. That seems like a smarter use of our money.

Imagine if profit statements included the costs of illness attributable to the profits. The use of pesticides might be restricted to emergency circumstances and PVC piping would be replaced with nontoxic, greener alternatives.

This truer accounting system would lead to investment in cleaner agriculture and manufacturing, and end the taxes of carbon and pollution that we already pay for our current lifestyles.

Even if the overall costs end up being the same, I’d rather spend our money on cleaner industry and infrastructure instead of on chemotherapy and asthma inhalers. Wouldn’t you?