First published in the Guardian, February 17th, 2014

Something – maybe a bat, although nobody was certain – recently bit my good friend Arnie. What happened next is an allegory for how short-term fixes can really screw up a system, whether it’s an ecosystem or an immune system or, while we’re at it, a financial system.

Erring on the side of caution, Arnie (not his real name) got the rabies vaccine, which consists of five shots. Shot number one went fine. But after shot number two, he immediately started feeling sick – his symptoms resembled the flu, but with some weird neurological symptoms – and he ended up in the emergency room.

A Benadryl drip seemed to relieve him somewhat, and he went home, still feeling pretty bad and non-functional, but not feeling like he would crumple into a ball on the floor. Then Arnie got the third shot, and got even sicker. I wanted to know why Arnie was so sick … scary sick. So I took to the internet and learned about adverse responses to rabies shots, how rare they are and, also, how serious they can be – kind of like a black swan event for business.

Twelve days after the initial shot, Arnie asked me to meet him at the emergency room because he thought he would pass out. He could barely move or keep his eyes open. At the hospital ER, the doctors seemed perplexed and checked for the “emergent” problems. Did he need to be intubated, coded, operated on? None of the above.

The doctors hydrated him and offered more Benadryl. Then they brought him steroids, which they explained would make him feel much better. I intervened directly – in fact, I stepped in front of the nurse to physically prevent the administration of the steroids.

I kept reminding the ER doctors that this severe adverse reaction was part of a longer-term response to the rabies vaccine and asked whether adding such potent systemic-altering drugs could complicate the problem. They couldn’t answer my question; they were focused on treating his symptoms and insisted that steroids would make him feel better in short order. I’m sure they would have. But nobody could tell me what they would do in the long term.

Finally, the hospital’s head of infectious diseases got involved, and agreed with me that the long-term risks of steroids far outweighed the short-term gain. Arnie would have to tolerate about three months of illness. He has now recovered, without the help of steroids.

Why am I writing about this saga in Guardian Sustainable Business? Just as steroids might have made Arnie feel better in the short term, strong quarterly earnings can make a business look great – potentially at the risk of ill effects in the long term.

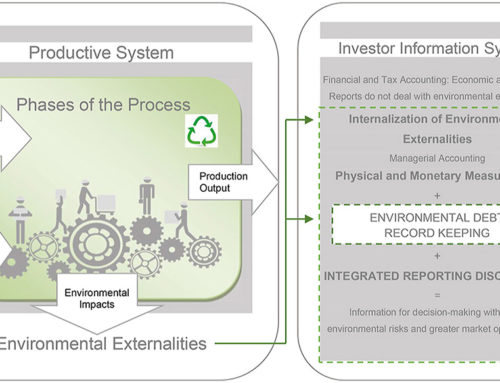

Sometimes, great quarterly earnings result in environmental degradation – which, in turn, can lead to financial degradation. One day your coal assets look hardy on your books, and the next year they look like stranded assets. As I note in my book, Environmental Debt: The Hidden Costs of a Changing Global Economy:

Ratan Tata recently admitted that the energy from his company’s new massive coal power plant in India will bring energy to market at roughly the same price as new solar. Tata actually described this plant as a ‘non-performing asset’ due to the increasing unavailability and high cost of coal.

Tata is undoubtedly one of the world’s smartest businesspeople, and he certainly made this coal investment with due diligence and the smartest engineers. But they overlooked – or underplayed – the environmental risk in assessing coal’s future value.

Conversely, quarterly earnings can be the result of brilliant strategic investments that will save money, waste, water and energy to sustain financial health in the long term. If a company or regional utility invests in a smart grid that empowers renewable energy sources, it will cost more than cheap, subsidized natural gas or coal, but can be the foundation for future environmental, national and financial security.

Google’s aggressive – and expensive – investment in renewable energy provides the company with urgently needed energy stability over the long haul. Other IT companies are now following suit. This is not a do-good investment; this is basic long-term strategy.

The current approach is like being treated by a surgeon who fixes your knee or cuts out your cancer, but knows nothing about how surgical changes fit into your overall life, health and pain management. This shortsighted and siloed approach governs most analysis and evaluation of business.

We look at numbers that do not reflect the world that business inhabits, only the business as a separate entity. Most financial research now separates environmental, social and governance issues into a separate less-important part of overall findings. This ignores how the financial and environmental crises are inextricably connected, and we ignore one or the other at our peril.

Our bodies are miraculous arrangements of billions of cells residing in a wondrous web of nature. Everything we do and use and feel and express are parts of this web. Nothing is separate. Keeping these connections in mind can help heal our bodies, as well as our businesses.