First published in The Guardian, July 10, 2013

Our financial and environmental crises are inextricably connected – both in the causes and solutions. Much too often, one corporation’s actions and assets become liabilities for other parties – taxpayers, businesses, families and natural ecosystems. I call this “environmental debt”, and it is as risky for financial security as subprime mortgages wrapped in credit default swaps. These are the connections we do not yet account for properly.

For example, in 2011, floods in Thailand effectively shut down the country. These intense storms became catastrophic because of massive deforestation, much of which occurred in the 20th century. Without enough trees, the ground was unable to soak up the floodwater. Local Thai factories that produced car parts were closed for months. These closures caused shortages for Toyota and Honda, and both companies were forced to suspend manufacturing in Kentucky, Singapore and the Philippines. Toyota alone lost production of 260,000 vehicles (3.4% of its previous annual output) and tens of thousands of workers lost their jobs in several countries.

Logging in 20th century Thailand caused financial havoc around the world in 2011 – a good 20 years after much of it occurred. The people of Thailand, several governments, numerous companies and shareholders from around the world all paid the logging’s environmental debt.

The financial industry is beginning to debate climate change risk management and disclosure. The Investor Network on Climate Risk is a network of more than 100 institutional investors with collective assets totalling about $11tn. Its parent organisation, Ceres, just released ablueprint for investors which states: “Institutional investors and their investment managers must integrate the financial risks from climate change, resource scarcity, supply chain failures and tighter water supplies into their investment practices if they are to be successful in the 21st century.” And several leaders in the insurance industry, at serious risk from extreme weather, are suggesting the same. It’s a smart start. Let us hope Ceres and its members have the clout to move this aspiration blueprint to actionable changes in global investment.

Even though this connection between our environmental practices and financial wellbeing is witnessed regularly across the globe, political and business leaders most often still urge each other and the public to ignore environmental constraints in order to solve immediate economic woes. Sometimes, the folly of prioritising short-term profit over long-term value is very evident. China became a world economic power in one generation, and in April 2013, it announced that environmental degradation costs 3.5% of its annual GDP. All money is not created equal. Paying for environmental degradation is not a constructive or desirable piece of any nation’s GDP.

Other countries have not made similar pronouncements to China’s, but certainly, environmental consequences account for a not-inconsequential piece of global GDP. Extreme weather’s heavy touch on public and private budgets ranges from firefighting and crop insurance in drought-stricken areas, rescue services in flood zones, higher prices for commodities for companies and consumers, and the huge expense of rebuilding infrastructure following natural disasters. These are all big-ticket items, and their intensity and frequency are all exacerbated by climate change.

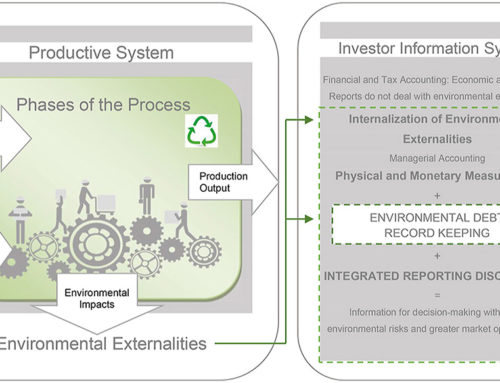

Despite initiatives by private banks such as the Equator Principles and the World Bank’s Natural Capital Project, project and investment financehave not changed much. No company or investor is yet paying for its pollution, and until these costs are embedded into basic operating accounts, the best intentions do not hold sway. But these initiatives have the potential to become the cornerstones for the new business model needed.

In November 2011, Puma became the first multinational corporation to create an integrated report that converted environmental information and data into monetary terms. Its 2010 environmental profit and loss account, produced by PricewaterhouseCoopers and TruCost, demonstrated that 72% of Puma’s profits would have disappeared if the company had paid for its environmental impacts. The report was hugely imperfect (as all accounting systems are) and an improved version is under way now. PPR, Puma’s parent company, has also promised to create environmental profit and loss accounts for its entire group of luxury brands (Gucci, Yves Saint Laurent, etc.) Other multinationals are also following suit. The businesses are ahead of the investors in sticking their necks out.

Current accounting rules and the financial industry’s obsession with quarterly reports fail all of us by limiting the best instincts of the best businesses. PepsiCo recently built a state-of-the-art factory in Arizona, and its innovations included net-zero energy and waste and a 75% reduction in water usage compared to plants of similar size. But the company is only deploying some of these brilliant engineering improvements in its factories around the world because these new technology changes are expensive. If water, energy and waste cost their true prices, Pepsi would be at an advantage for its innovation, as opposed to having to defend its decision to spend money on smart engineering and protocols.

Changing accounting and reporting rules so that the biggest polluter no longer makes the biggest profit would create a more resilient economic system as well as ecosystem. The two are completely symbiotic.

I propose a new framework to guide 21st century commerce. Pollution can no longer be free nor subsidised and the long view should guide all decision making and accounting. The government needs to play a vital role in catalysing clean technology and growth while preventing environmental destruction.