First published in the Huffington Post, April 9, 2013

China admits to having a big problem. This admission alone is big news. China’s own Ministry of Environmental Protection now estimates the costs of this degradation at $230 billion for 2010, or about 3.5 percent of its Gross Domestic Product. (This estimate came before Beijing’s recent air quality crisis and the 15,000 dead pigs found floating in Shanghai’s water supply.) As Americans, we are a large part of China’s professed problem — both the causes and the solutions. Much of this pollution is caused by China’s huge consumption of the coal-fired energy that keeps its factories running round the clock as well as the manufacturing process itself.

How much of China’s exports go to the United States? In 2011, China exported $400 billionof goods to the United States and imported $104 billion of our goods, giving China a $300 billion trade surplus and United States politicians and economists agita. In 2009, according to the WTO, 25 percent of China’s total exports went to the United States. How much of China’s pollution is created by American demand and consumption of cheap Chinese goods, from clothing to computers and everything else?

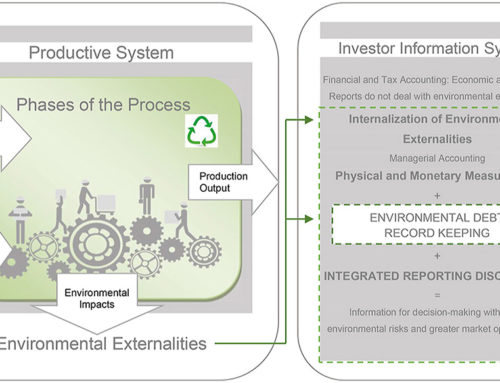

But herein lies the opportunity. Right now, we do not pay the real price of any of our goods because we are not paying for their environmental degradation. But the Chinese government is now debating how much to spend on remediation, how much to spend on changing factories and electrical plants to cleaner technologies, and how much to spend on new agricultural practices. Numbers in tens of billions of dollars are being tossed around as necessary expenditures for protecting the country from untenable losses of viable water, land and air. There is a visceral understanding in China that these environmental losses could translate to economic and social chaos all around. So why aren’t Americans having the same debate?

Americans are not so good at tackling cost/benefit analysis when it comes to economic growth or employment opportunities. Now that China is publicly discussing how environmental losses threaten its very stability, why not begin an honest debate in the United States about our own environmental debt? In recent testimony before the U.S. House Judiciary Committee, William L. Kovacs, Senior Vice President of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce said: “Regulations impact jobs in three ways: they impose significant compliance costs that divert resources away from other needs; they can cripple or even destroy industries; and they can impose such complexity that they discourage business expansion and job creation. To bring manufacturing back to this country, we must understand the impacts of excessive regulations.” It is absolutely true that government regulations are often implemented with a Kafkaesque logic that has neither common sense nor acceptable timelines. But U.S. industry has been fighting environmental regulations since 1972 when Mobil ran a full page ad in the New York Times claiming that the Clean Air Act was a $66 billion mistake ($366 billion in 2013 dollars).

The radical 1970s Clean Air Acts are the only reason that the air in American cities does not resemble the air in most Chinese cities. And it’s not as if we don’t have terrible air and water problems in the U.S. We do. They’re just not as bad as China’s today, although Salt Lake City recently endured a month-long health emergency due to bad air. I live in NYC where the air is often disgusting and dangerous on a regular basis, especially in the summer. This pollution raises health care, education, sanitation and water costs.

There is no clear consensus on how much pollution really costs. But if China openly states that it’s a 3.5 percent hit on its GDP, why don’t we seize the opportunity to re-value our economy and GDP? British economist Nicholas Stern estimates that just to combat climate change, western economies should now be spending 3.5 percent of GDP per annum. Imagine if China and the United States led a global negotiation to fund and build global renewable energy infrastructure at the same time? Imagine if China and the United States led a global negotiation whereby companies that pollute least are rewarded for their positive environmental investments and companies that pollute most are charged. The EU’s decade of experience in this kind of spending can help provide the outlines of a path.

Under no circumstances can pollution remain free. Why don’t we actually try to make this fundamental change to the underpinnings of global trade WITH China? As China is faced with a dire environmental crisis, the cold war’s Mutual Assured Destruction has taken on a new form. We cannot outspend the Chinese to avert climate change and environmental disaster. We must embark on a path of Mutual Assured Survival.

Hundreds of multinational corporations that manufacture in China (and in the rest of the world) would like to embark on this path. They are constrained now because the biggest polluter currently has the financial advantage. It is in all parties’ interests to change that. I think the Chinese government would now agree. Mr. Kerry, are you ready to negotiate a deal that would benefit the planet as well as the global economy? Let’s use this crisis to negotiate an end to the era of cheap goods and the beginning of the era of sustainable goods.