For the Yom Kippur holy day – the spiritual case for climate action

I’m not sure about God, but I do believe there is godliness in nature. It is a sacred gift that is awesome – in the sense that this word is used in scriptures of all faiths. As a decades-long climate change activist, I am convinced that we will only save our planet if we insert our souls into the story.

Whether you view nature as God’s ultimate creation, as humankind’s dominion, or like me, as the astonishing wonder of the spiritual and physical realm, nature is under dire threat. The extraordinarily complex web of life is dying around us, and as fixing it will disrupt our physical and spiritual equanimity, we largely ignore this suffering.

On October 5th, observant Jews around the world will mark the holiest day of the year, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. The purpose of #yomkippur is to effect individual and collective purification by the practice of forgiveness of the sins of others and by sincere repentance for one’s own sins. Rituals include a 24 hour fast and a break from work and technology – pathways to dedicate oneself to sincere and deep reflection.

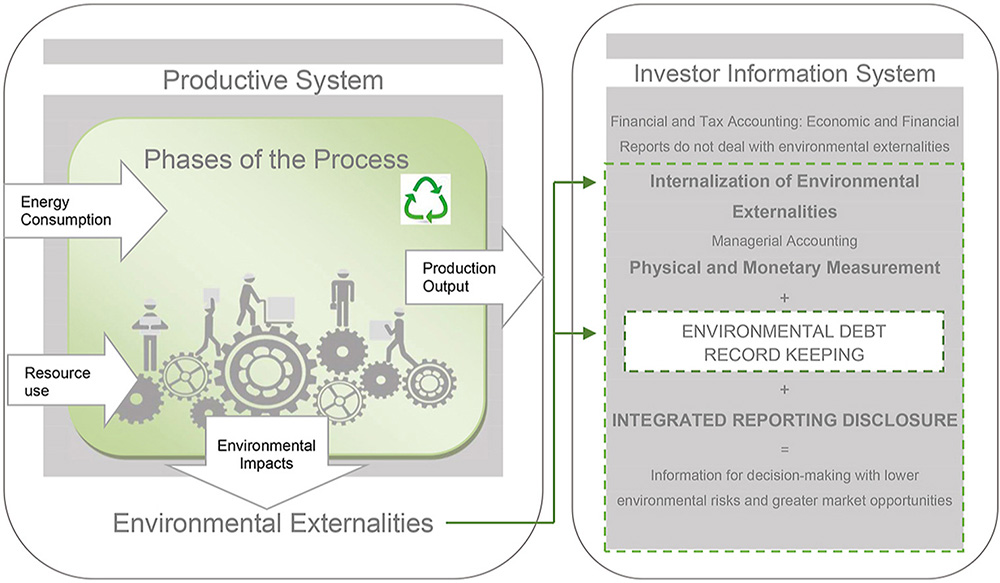

I was raised by a secular Jewish family in New York City, where around 20% of those who identify as Jews in America reside. The second largest Jewish community in America is in South Florida, brought to its knees by Hurricane Ian. #hurricaneian ‘s intensity is a result of our collective failure to address the environmental debt of decades of fossil fuel use and our witting abuse of nature.

The term Tikun Olam, in Jewish scripture, means to do something with the world that will not only fix any damage, but also improve upon it.

According